Project Description

The Images are unique and original photograms and cyanotypes all 40x50cm. As the exhibition toured to different venues and the images were sold, another one had to be created, hence some letters have more than one artwork. The book “The love letters of a Chinese lady” was privately published in Edinburgh in 1917. The “lady” was Lui Kwei-li, a 19th Century Chinese woman living in the ancestral home of her husband, high on the mountain-side outside the city of Su-Chau.

Kwei-li is 18 years old, and in the first years of her marriage when her husband is required to accompany Prince Chang on a diplomatic mission overseas. A selection of the letters she wrote to him are contained in this suite of photograms. Of course it was quite extraordinary that she could read and write – and she outraged her mother in law by doing so. Education in a woman was not seen as desirable. As a child Kwei-li had been taught these skills, alongside her brothers, and one can only assume Kwei-li’s father was a very enlightened person. Kwei-li was a highly intelligent and compassionate woman, and her observations of life – from domestic to spiritual – are as relevant today in the year 2002, as they were when written.

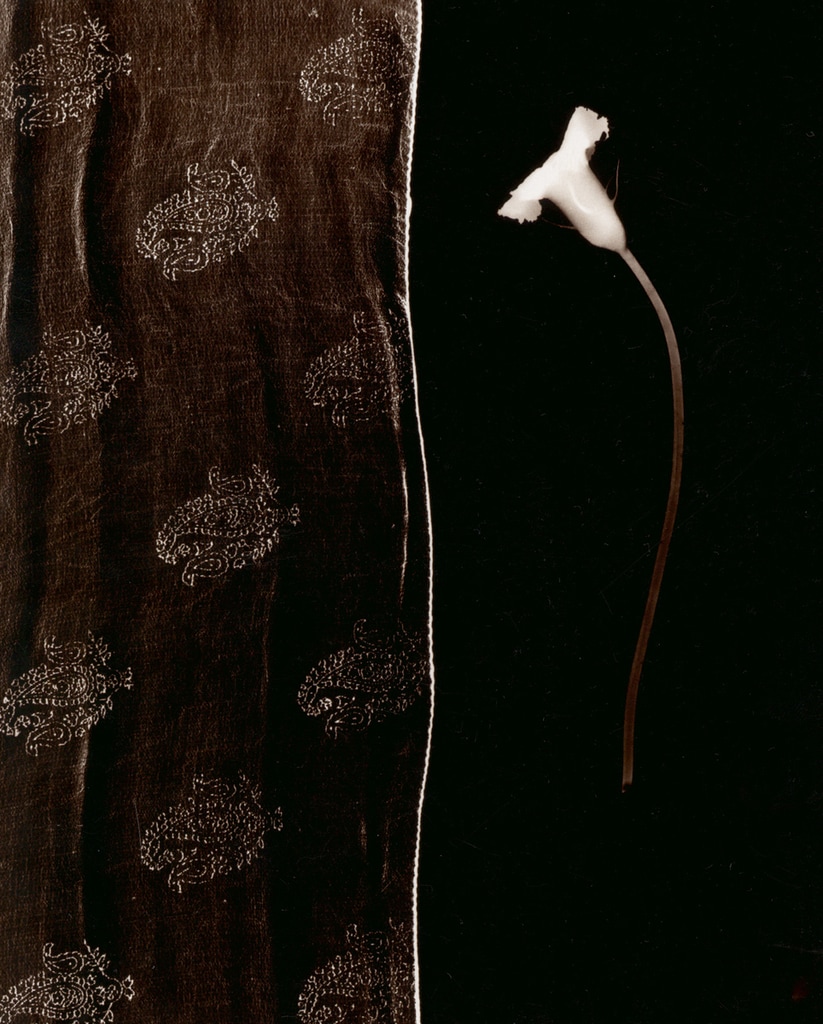

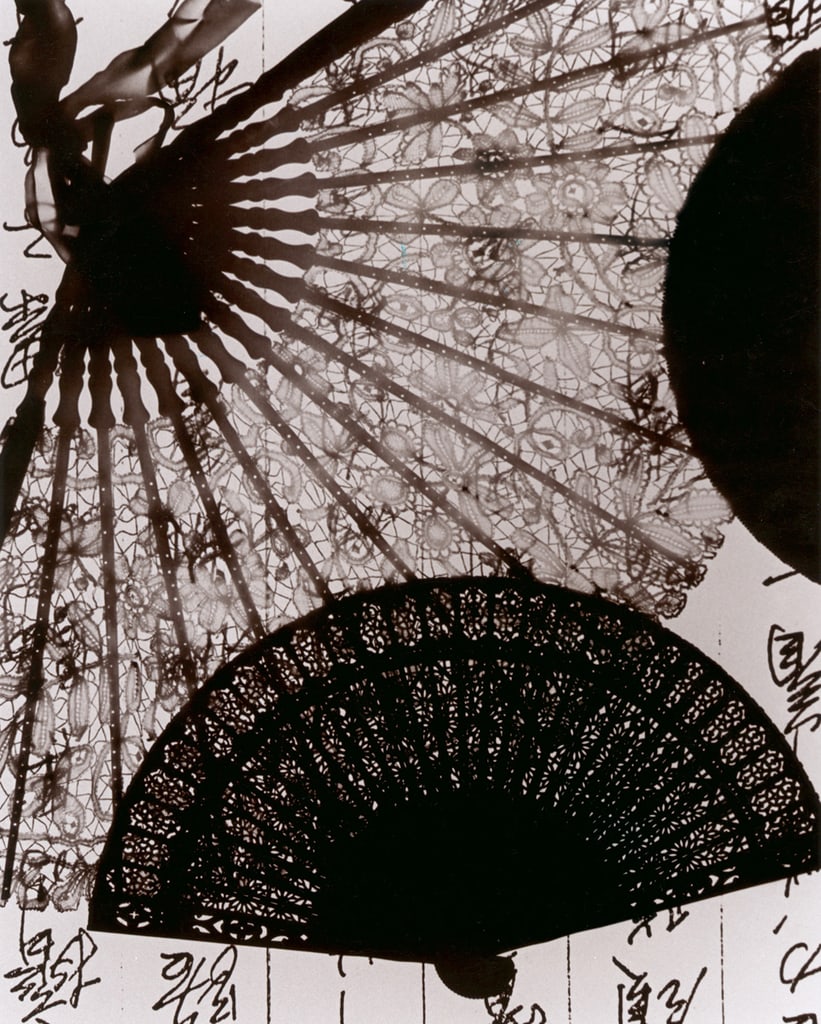

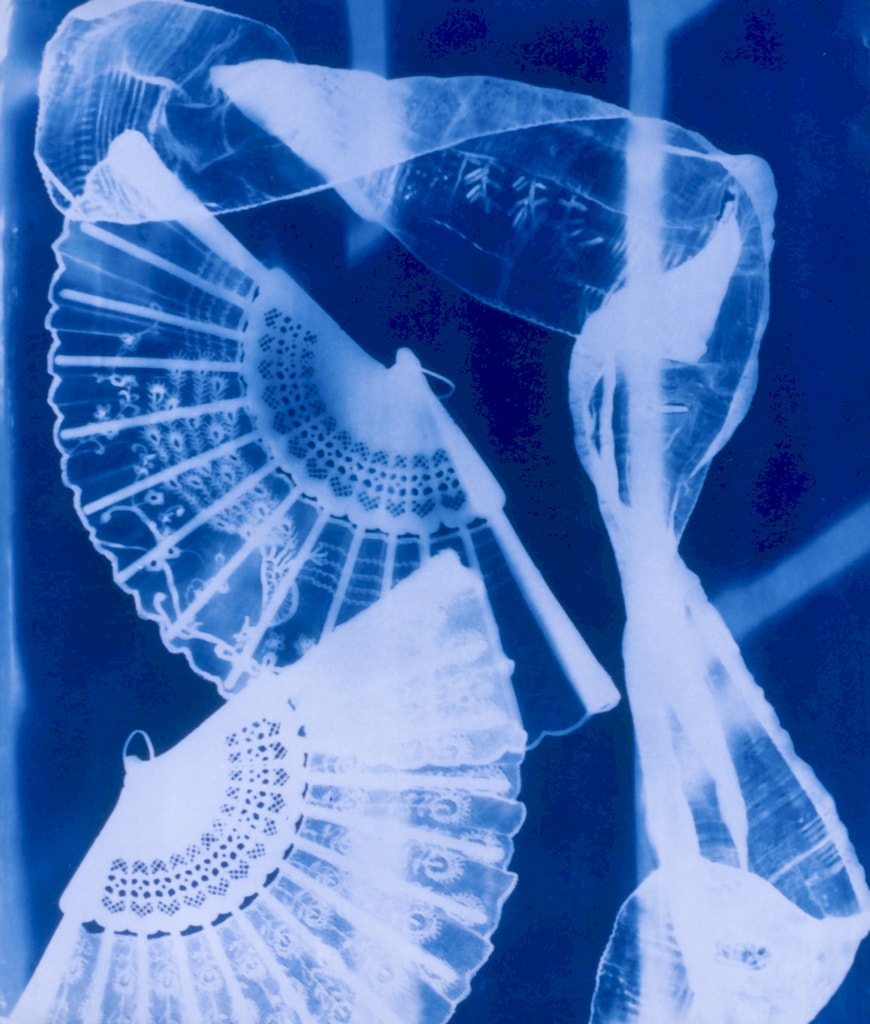

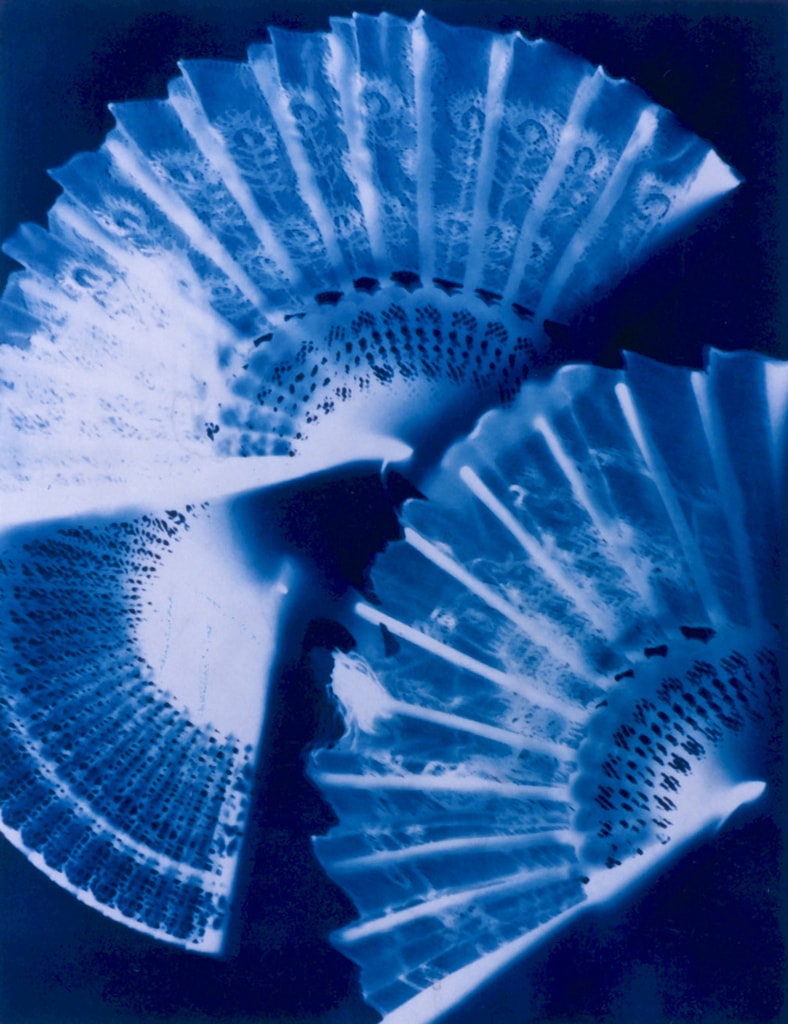

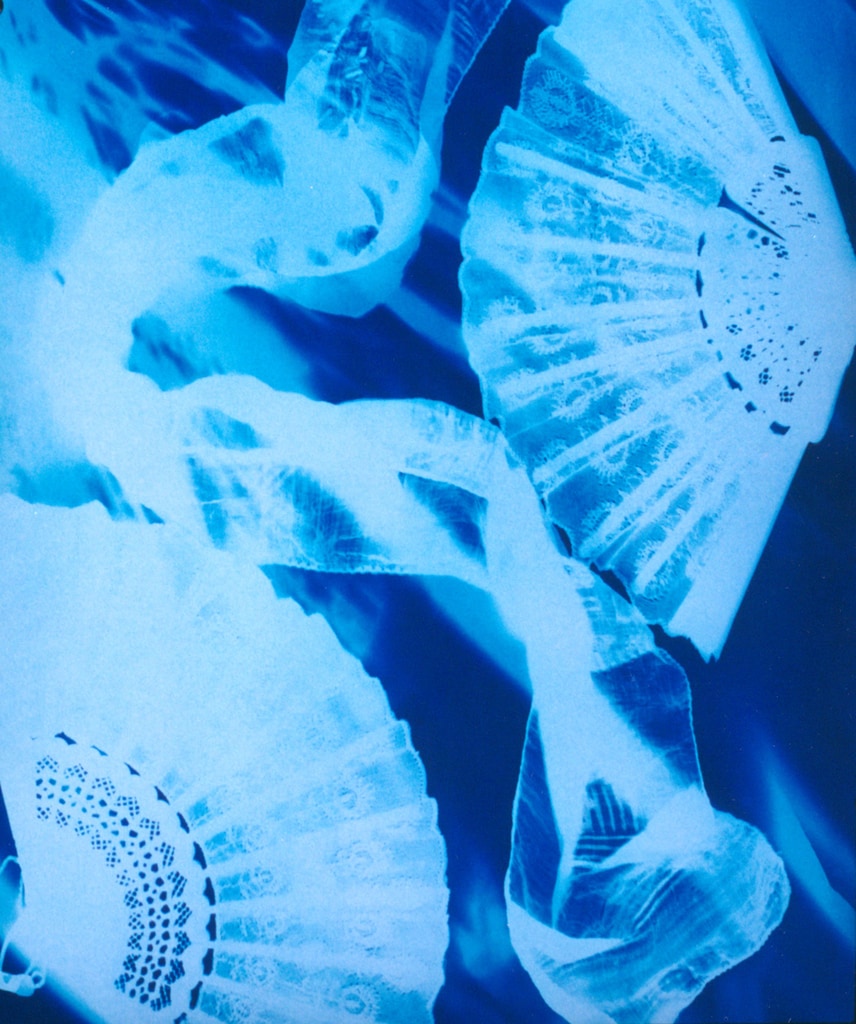

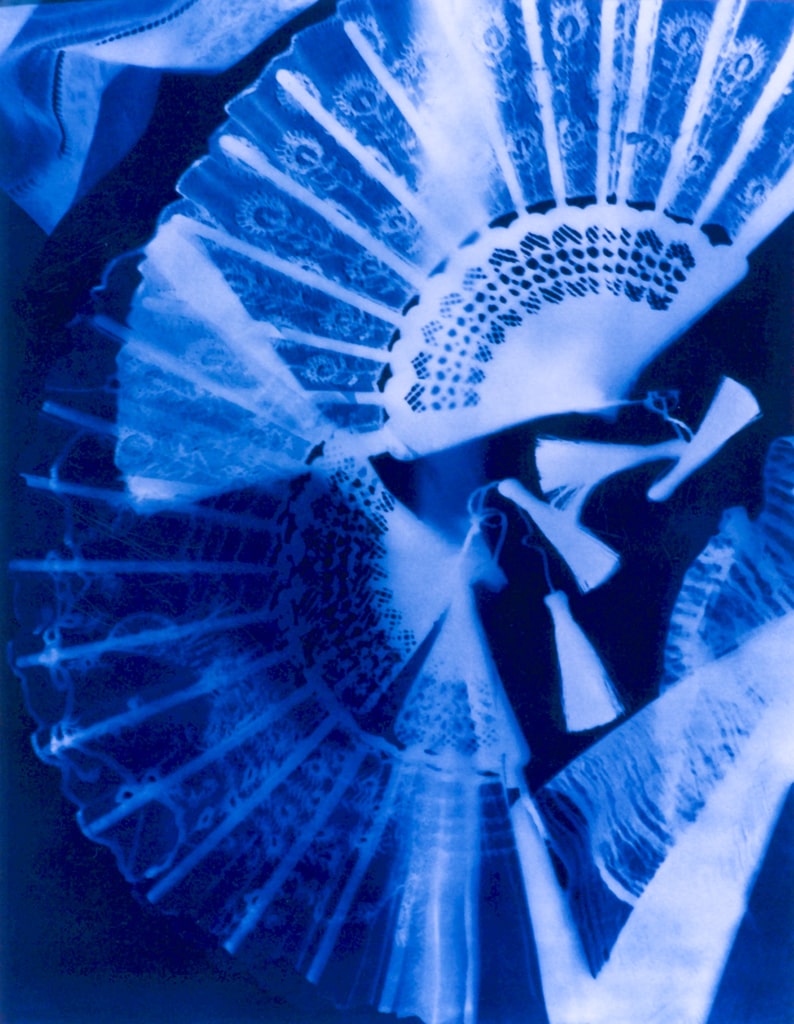

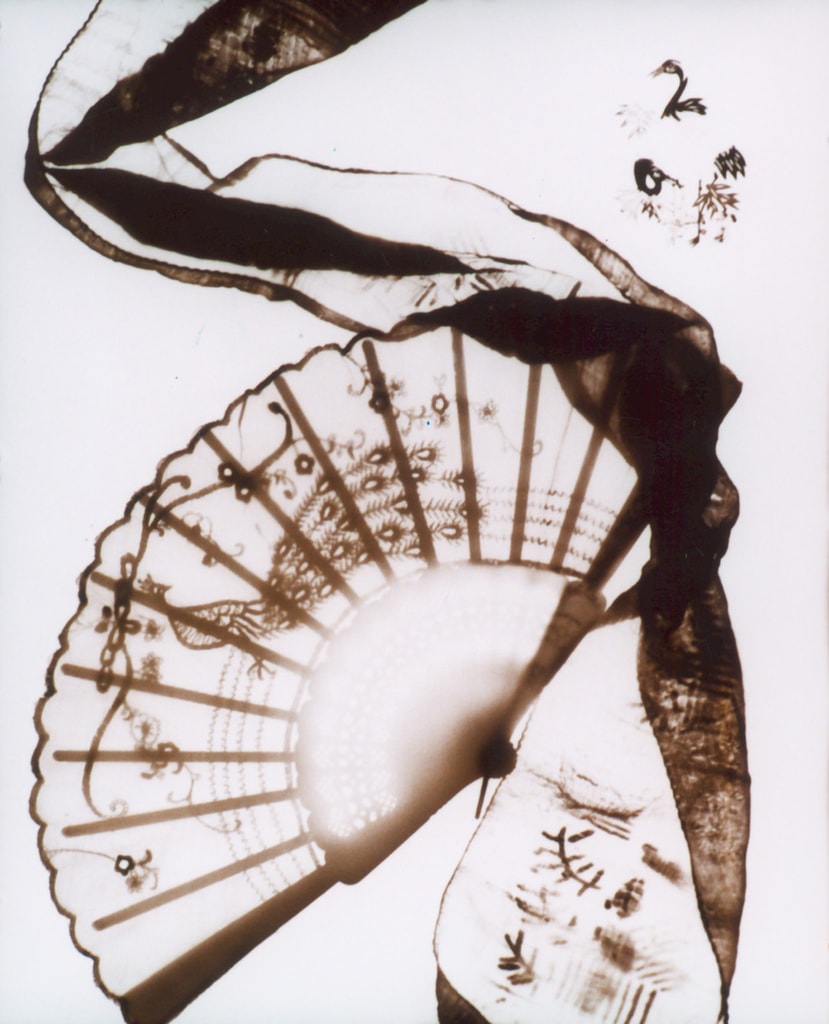

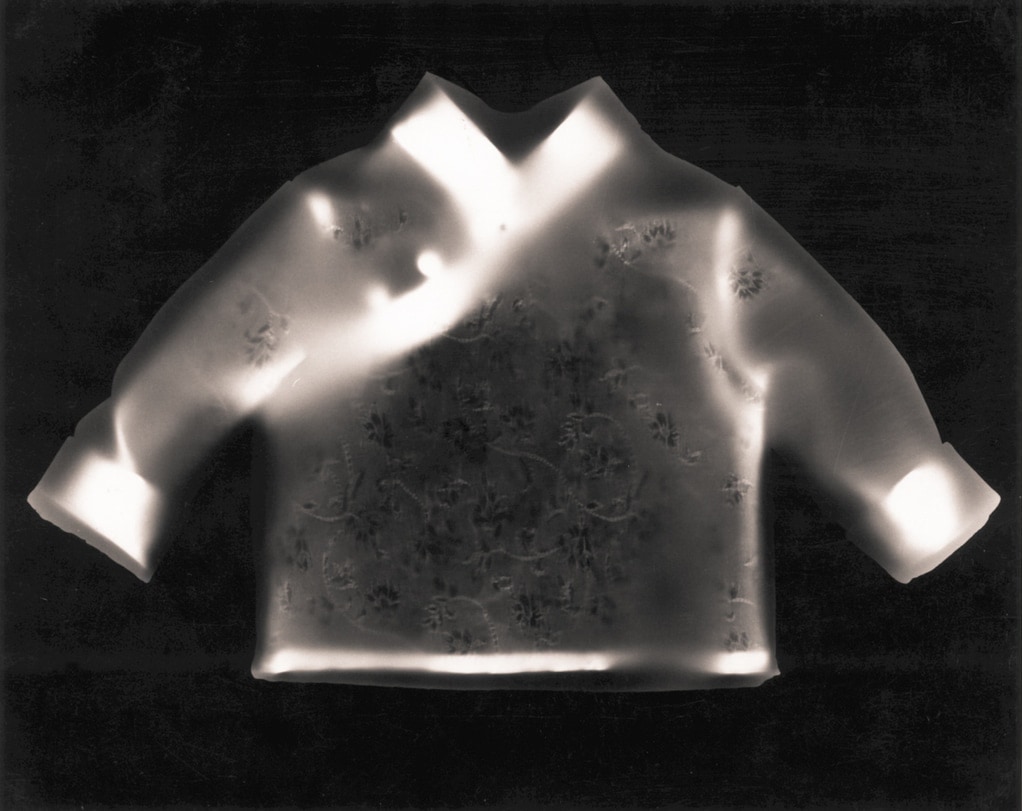

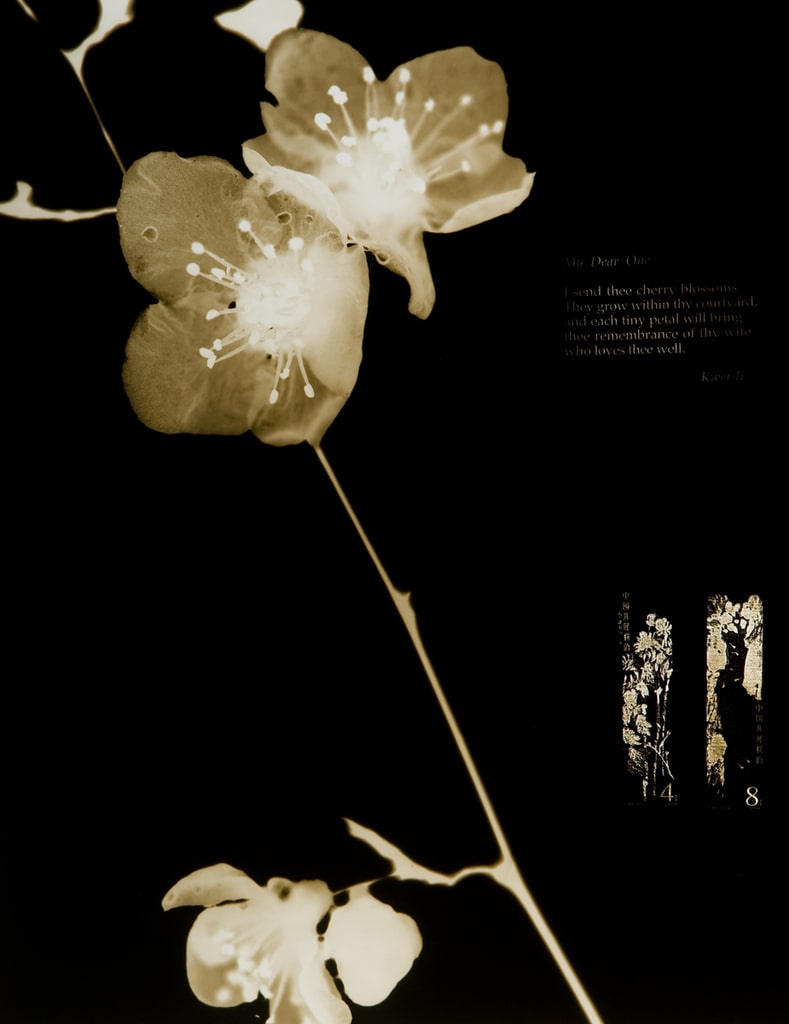

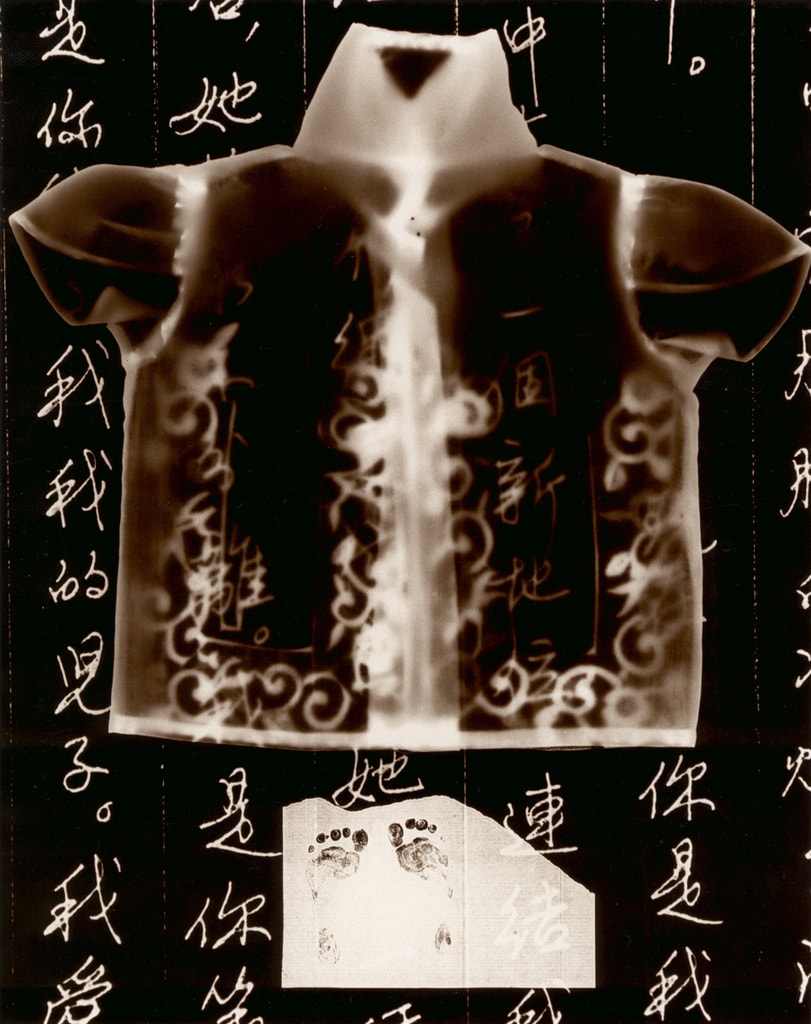

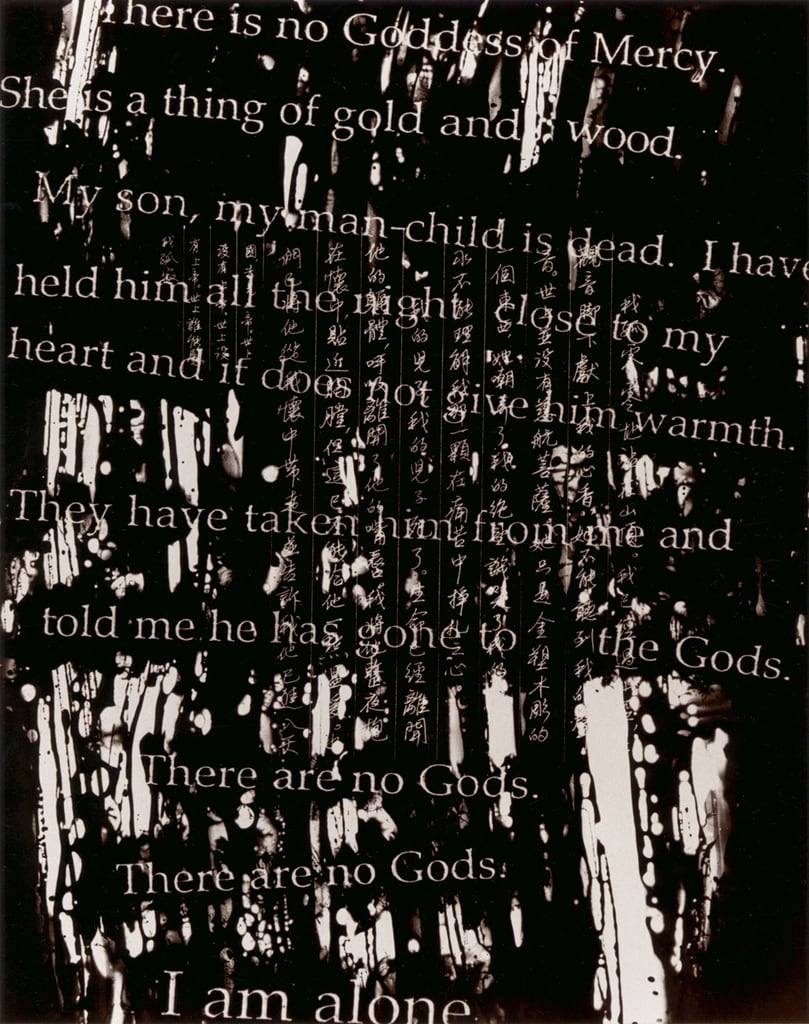

I have selected 9 of these letters and present them as a text panel and an image panel. Chinese stamps have been used in conjunction with the letters and on some of the image panels. I have used the photogram technique – ie placing an object directly onto photographic paper and exposing it to light. A camera is not used. Film is not used. Each image is unique and cannot be reproduced.

Some of the letters have been translated back into the original Mandarin, and these symbols have been integrated into the imagery.

My Dear One

My first letter to thee was full of sadness and longing because thou were newly gone from me. Now a week has passed, the sadness is still in my heart, but it is buried deep for only me to know.

It is beautiful here now. The hillside is purple with the autumn bloom and the air is filled with a golden haze. Mah-li and I take our embroidery and sit upon the terrace, where we pass long hours watching the people in the valley below.

From the terrace I watched thee when thou went to the city in the morning, and it was where I waited thy return. Because of my love for it and the rope of remembrance with which it binds me, I keep it beautiful with rugs and flowers.

I long for thee. I love thee. I am thine.

Thy wife

My Dear One,

A new slave-girl has come into our household. As thou knowest, there has been a great famine to the north of us, and the boats, who follow all disaster, have been anchored in our canal. I do not know why thine August Mother desired to add one more to take of rice beneath our roof-tree; but she is here. She was brought before me, a little peasant girl, dressed in faded blue trousers and a jacket that had been many times to the washing pool. In her black hair she had stuck a pumpkin blossom. She told me there were many within their compound wall. The rice was gone, the heavy clothing and all of value in the pawn-shop. Death was all around them, and they watched each day as he drew nearer – nearer.

Then came the buyers of girls. They had money that would buy rice for the winter and mean life to all. but the mother would not listen. She was told over and over that the price of one would save the many. But she would not sell her daughter. Her nights were spent in weeping and her days in fearful watching. At last, worn out, despairing, she went to a far-off temple to ask Kwan-yin, the Mother of Mercies, for help in her great trouble. While she was gone, Ho-tai was taken to the women in the boat at the water-gate, and many pieces of silver were paid the father. When the stomach is empty, pride is not strong, and there were many small bodies crying for rice that could only be bought with the sacrifice of one. That night, as they started down the canal, they saw on the tow-path a peasant woman, her dress open far below her throat, her hair loose and flying, her eyes swollen and dry from over-weeping, moaning pitifully, stumbling on in the darkness, searching for the boat that had been anchored at the water-gate; but it was gone. Poor little Ho-tai! She said, “It was my mother!” and as she told me, her face was wet with bitter rain. I soothed her and told her we would make her happy, and I made a little vow in my heart that I would find that mother and bring peace to her heart again.

I am thy wife who longs for thee.

Kwei-li

My Dear One,

All thy women-folk have been shopping! A most unheard of event for us. We have Li-ti to thank for this great pleasure, because, but for her, the merchants would have brought their goods to the courtyard for us to make our choice.

We were a long procession. First thine Honourable Mother with her 4-bearer chair; then your most humble wife, who has only 2 bearers – as yet; then Li-ti, followed by the chairs of the servants who came to carry back our purchases. It was most exciting, as we go rarely within the city gate. It was market day and the streets were made more narrow by the baskets of fish and vegetables which lined the way. They all stepped to one side at the sound of the A y-yo of our leader, except a band of coolies carrying the monstrous trunk of a pine tree, chanting as they swung the mast between them, and keeping step with the chant. It seemed a solemn dirge, as if some great giant were being carried to the resting-place of the dead.

But sadness could not come to us when shopping, and our eager eyes looked long at the signs above the open shopways. From the fan-shop hung delicate, gilded fans; and framing the silk-shop windows gaily coloured silk was draped in rich festoons that nearly swept the pathway.

That crowded, bustling, threatening city seems another world from this, our quiet, walled-in dwelling. I feel that here we are protected, cared for, guarded, and life’s hurry and distress will only pass us by, not touch us. Yet we like to see it all, and know that we are part of that great wonderthing, the world.

Thy wife

My Dear One

I have received thy letter telling me thou wilt not be here until the summer comes. Then, I must tell thee my news.

I am jealous of this paper that will see the delight and joy in thine eyes.

I say, “Perhaps when you return, I shall be the mother of a child.” Ah! – I have told thee. Does it make a quick little catch in thy breath? Does thy pulse quicken at the thought that soon thou wilt be a father?

Thou wilt never know what this has meant to me. It has made the creature live that was within my soul, and my whole being is bathed with its glory.

My courtyard is filled with the sounds of chatting women.

I have sent for the sewing-women and those who do embroidery, and the days are passed in making little garments.

The piles of clothing grow each day, and I touch them and caress them and imagine I can see them folding close a tiny form. There are jackets, trousers, shoes, tiny caps and thick warm blankets.

I send for Blind Chun, the story-teller, and he makes the hours pass quickly with his tales of bygone days. The singers and the fortune-tellers all have found the path that leads up to our gateway, knowing they will find a welcome.

I am

Thy Happy Wife

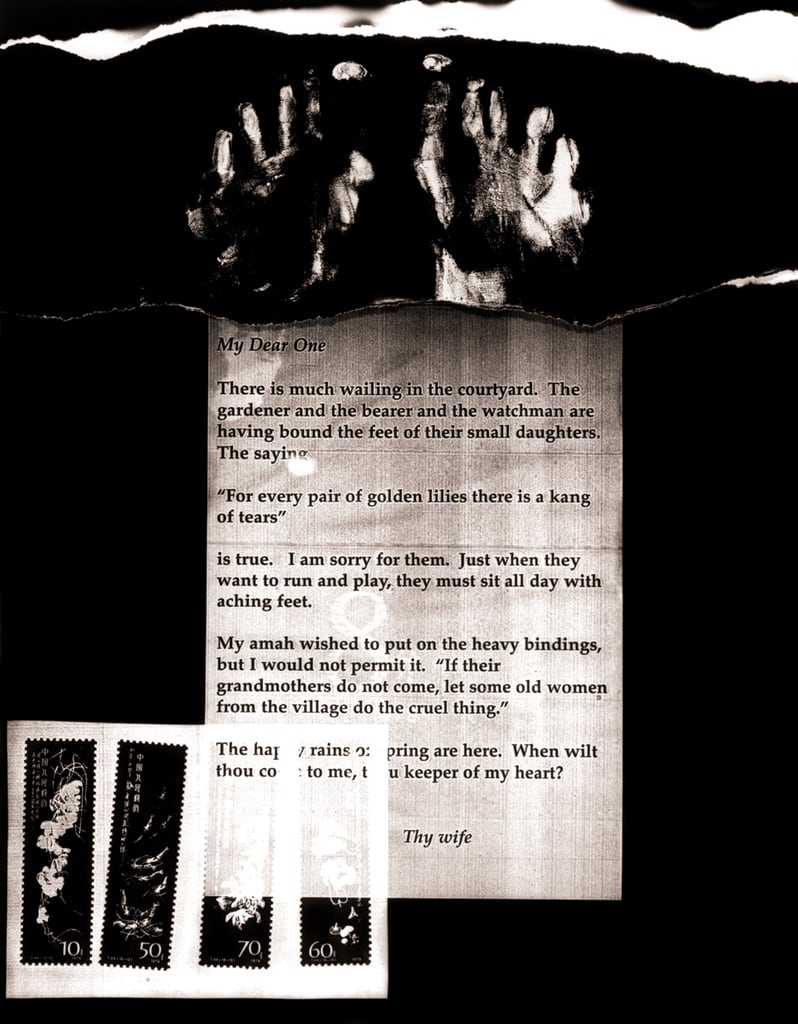

My Dear One

There is much wailing in the courtyard. The gardener and the bearer and the watchman are having bound the feet of their small daughters. The saying

“For every pair of golden lilies there is a kang of tears”

is true. I am sorry for them. Just when they want to run and play, they must sit all day with aching feet.

My amah wished to put on the heavy bindings, but I would not permit it. “If their grandmothers do not come, let some old women from the village do the cruel thing.”

The happy rains of spring are here. When wilt thou come to me, thou keeper of my heart?

Thy wife

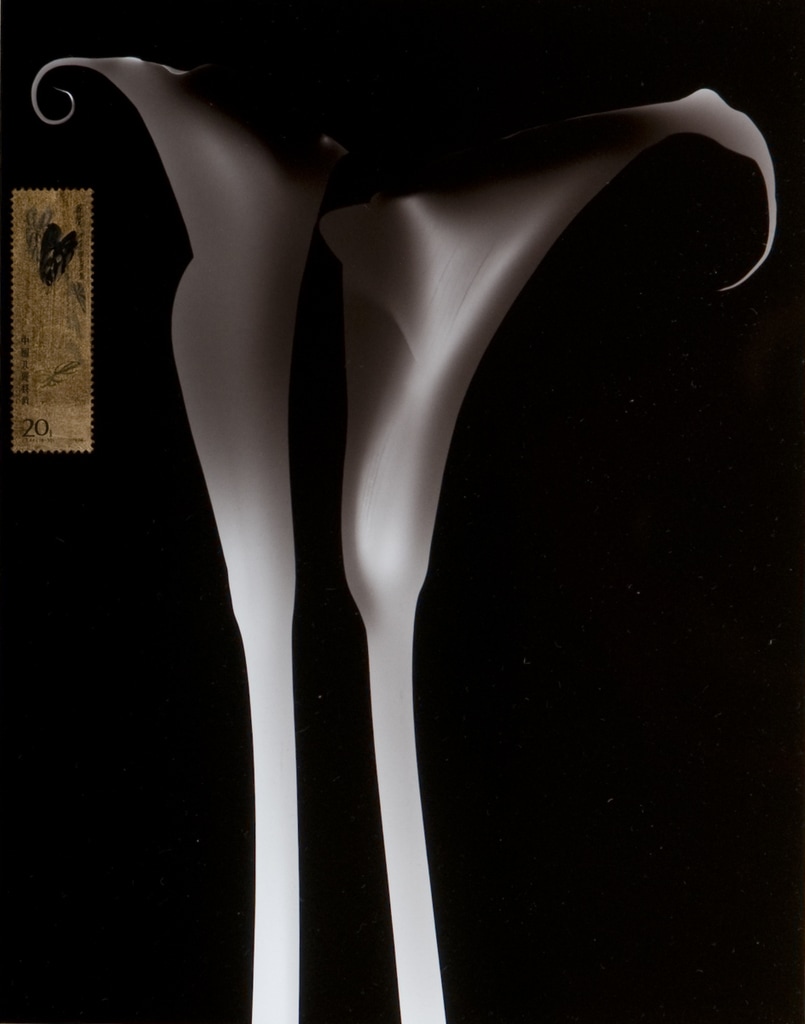

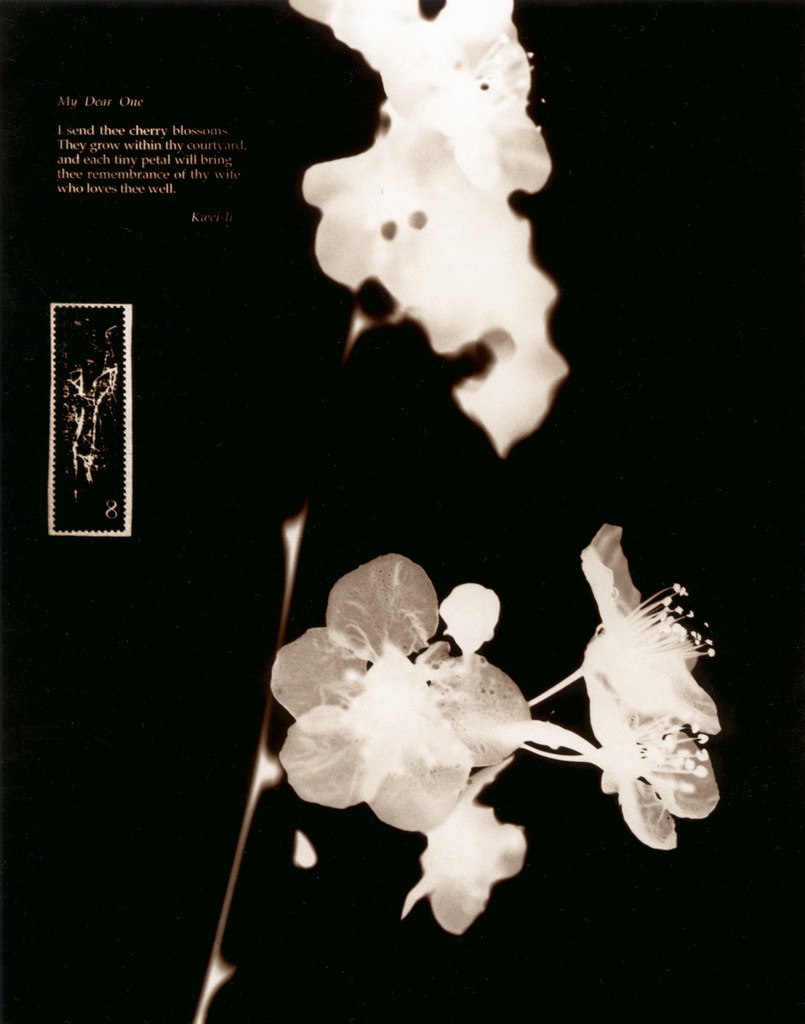

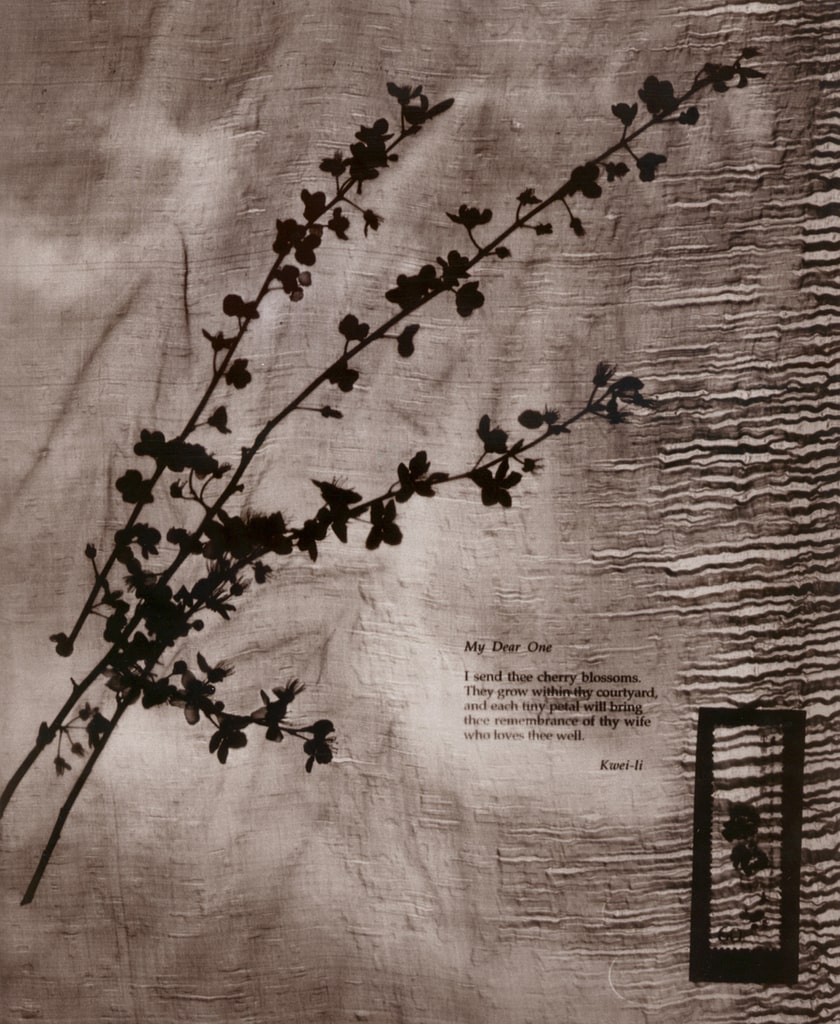

My Dear One

I send thee cherry blossoms. They grow within thy courtyard, and each tiny petal will bring thee remembrance of thy wife who loves thee well.

Kwei-li

My Dear One

He is here, beloved, thy son! I put out my hand and touch him.

Dost thou know what love is?

I thought I loved thee.

I smile now at the remembrance of that feeble fleeting flame. Now – now – thou art the father of my son, thou hast a new place in my heart. The tie that binds Our hearts together is a bond, a love bond, that never can be severed.

The Gods are good, my loved one, they are good to thy

Kwei-li

I am alone on the mountain top.

There is no Goddess of Mercy. She is a thing of gold and wood.

My son, my man-child is dead. I have held him all the night close to my heart and it does not give him warmth.

They have taken him from me and told me he has gone to the Gods.

There are no Gods. There are no Gods. I am alone.